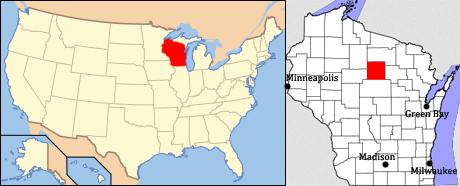

Wisconsin is a state in the north of the United States. Its capital is Madison, and the other major cities are Milwaukee and Green Bay.

However, our story of Wisconsin’s Latvians is not connected to the big cities, but rather the countryside. Over a hundred years ago, Latvians founded a farming colony in the north of the state and built the first Latvian Lutheran church in the US.

Many other northern Europeans – Scandinavians, Germans, etc. – had already made the northern states their home, and so Latvians living on the East Coast of the US also searched for a place to make their home in these regions.

Articles in Latvian newspapers such as “America’s Herald” (published in Boston) and “Homeland” (published in Jelgava) reflect society’s discussions and disagreements about the formation of a farming colony and its possible location, printed results of information-gathering expeditions and informed on the chosen place in Lincoln County, Wisconsin, near the villages of Gleason and Bloomville.Who are the Old Latvians?

At the end of the 19th century, many Latvians left their homeland and headed out into the world (to Inner Russia, Siberia, North and South America, Australia, etc.), looking for a better life – their own little piece of land, personal and political freedom.

The largest number came to the United States. The first immigrants settled in the big cities of the East Coast – New York, Boston, Baltimore and Philadelphia. Some stayed in the cities, but others – former landless peasants and farmhands – longed for the opportunity to own and farm their own land. They didn’t want to lose their Latvian heritage or connections to other members of the community, and thus they decided to look for a place where they could form a farming colony together, as many other immigrant communities had already done in the US.

Latvians moved to the US in other time periods as well – before and after the First World War, as well as the biggest wave, refugees fleeing Soviet occupation after the Second World War. Latvian immigration to the US started again after Latvia regained independence, and continues to this day. The Latvians who arrived after the Second World War started to call all of those who had come before them “Old Latvians”.

Farm life

Before the colony was founded, there were lots of disagreements and worries about whether the colonists would be able to endure the hardships that came with being a trailblazer in the virgin forests of the northern US. Regardless of the disagreements, at the end of 1897 the first colonists arrived in Lincoln County and started to buy land from the Wisconsin Valley Land Company.

Starting life in the virgin forests wasn’t easy – it took many years, a decade even, to cut down forests and prepare the land for farming. The oldest generations alive today still remember that as children they would be sent into the fields to dig out rocks before seeds could be planted. One of the main sources of income in the first years was selling logs, which was reduced by necessity as the forests were chopped down. In later years, colonists kept animals and farmed the land.

The land was fertile and in the 1930s the colony had well-kept and productive fields, good cows, there were good roads, as well as electricity and telephone service. Colonists owned four stores and three dairies.

Lutheran congregation and churches

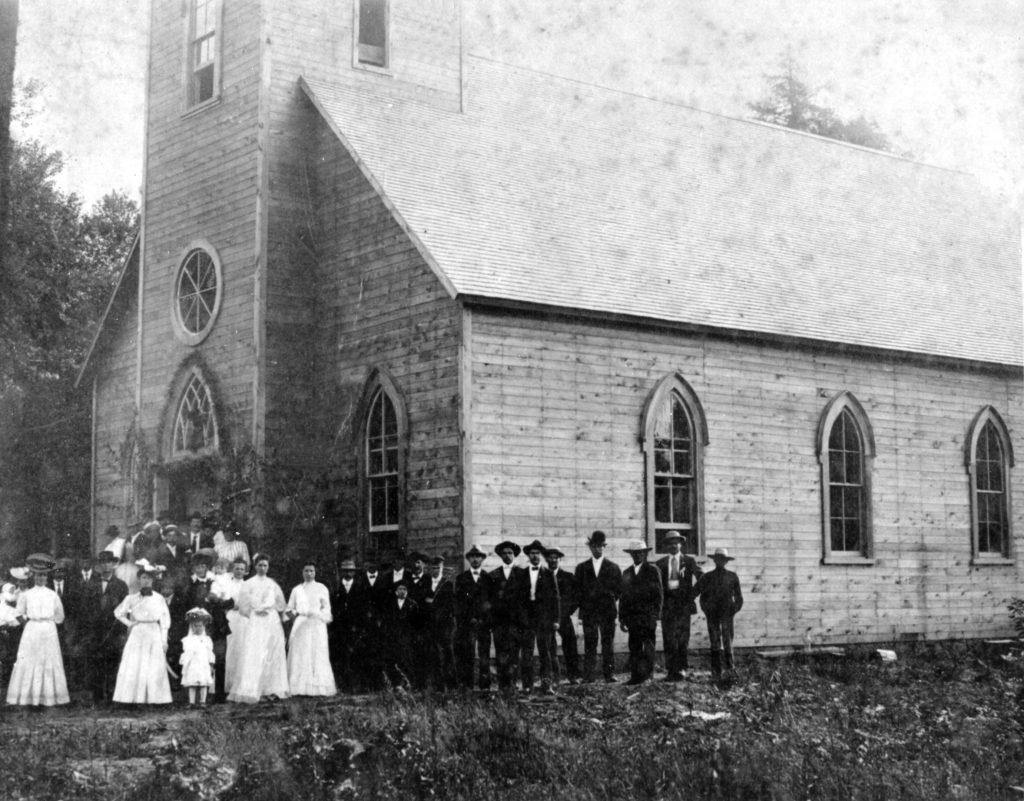

The Wisconsin Valley Land Company had promised that once 25 pieces of land had been bought, that they would donate 40 acres (1 acre is about 0.405 hectares) for a church and cemetery. The company kept this promise and in 1900 granted this land to the Latvian community. In this same year, 35 Latvians founded the Lincoln Latvian colony’s Evangelical Lutheran Martin Luther congregation.

By the middle of 1902, about 100 Latvians and 29 Estonians had moved to Lincoln County. At first, they considered creating a joint congregation, but this did not work out and the Estonians formed a separate congregation.Both congregations belonged to the Missouri Synod and were served until 1902 by traveling pastor Hans Rebane, who was born near Valka (on the modern Estonian-Latvian border). His mother was Latvian, his father Estonian, and therefore Rebane spoke both languages. In 1902, the Missouri Synod decided that the Lincoln congregations would fall under the auspices of the Canadian Baltic minister Joans Sillaks. The Lincoln residents were disappointed about this, for they already knew Rebane, who had been serving their community since the first church service in 1898. Regardless of the Synod’s decision, Rebane continued to serve the Lincoln congregations, where he also owned land, according to Vilis Kanapka. From 1910, the congregation was served by pastor Edvards Jurevics.

Lincoln County Latvians Križa, Lūsis, Arders, Venceslavs and Sommers built the church with their own hands. Other colonists, including Kaucis, Urbans and Sproģis, donated religious accoutrements, such as crosses, altar coverings and dishes.

The church was opened in 1906. It was the first – and for a long time, the only – Latvian-built Lutheran church in the United States, for many city congregations didn’t built their own churches, but used other congregations’ churches instead.

At the beginning of the 1930s, services took place in the Lincoln church twice a month. In 1951, the church was closed, and ten years later it was torn down. With the loss of the church, the colony lost its social centre.

Today, all that is left is the cemetery, where burials still take place. These burials are not only of Latvians from the Lincoln colony, but also members of the Second World War refugee community from other cities in Wisconsin.

After the church was torn down, the bell was gifted to the Minneapolis Latvian congregation, while the altar cross went to the Milwaukee St. Trinity Latvian congregation. It was still used at the beginning of the 2000s at cemetery festivals in the Lincoln cemetery, the tradition of which had been renewed by pastor Jānis Meistars in the 1950s. The cornerstone of the church came into the collection of the Latvians Abroad – Museum and Research Centre in Latvia in 2011.

Social life

Even though Latvians and Estonians could not come to an agreement about a common church, they were united in matters of national pride, which would come to bear at the local taverns and arguments with Americans. Local Americans called their colony the “Russian Settlement”, since the Latvians and Estonians were from the Russian Empire. Of course, this offended nationally-minded Latvians and Estonians who would make it known that they were not Russians of any kind.

While the long-term Latvian residents of Lincoln County were farmers, not all Latvians in the area were. Many Latvians also came to Lincoln County for work in the logging industry, however, once the forests were mostly cleared, they moved on to different places and jobs, not staying in the community.Even though the community was officially founded as a Latvian Lutheran colony, as time passed a small group of Baptists also established themselves. The most fervent Lutherans were not kindly disposed towards them, and Lutherans who were friendly towards them were held in suspicion by the wider community, because there were concerns that they would accept the Baptist’s “false teachings”.

After the 1905 Russian Revolution (which was particularly active in Latvia), a number of non-religious people arrived in the Lincoln colony. The colonists frequently regarded all non-religious people as socialists, though this was not always the case. There were socialists who arrived in the colony, however, their influence was not particularly large amongst the farmers – socialist agitators themselves admitted this. Socialist ideals gained more traction amongst the logging workers.

These divisions were also visible in the Latvian cemetery – the fervent Lutherans were buried on the hill near the church, while the non-religious – in the “pagan graves” by the roadside.

In 1903, Emīlija Keikule, a Latvian, had completed her teaching exams, and started to work in the local school. By the 1930s, all of the Latvian colonists’ children went to local American schools, and there was no instruction in Latvian.For a number of years, there was a Latvian library in the Lincoln colony. The remainders of this library was kept by Vilis Kanapka in the late 1950s, however, what happened to them later is not known.

There is not a lot of information about traditional Latvian celebrations in the colony, with the exception of Jāņi (Midsummer, St John’s Day). Descendants of the Bolder family remember Jāņi celebrations, and how once all of the beer was gone, they would send around a hat to collect money for the next round.

The decline of the colony

One of the biggest hurdles to the colony’s further development was that, with the exception of young families, who had arrived in Lincoln from the eastern cities, most of the colonists were bachelors. The Latvian community lacked young women, and so men either stayed bachelors or they had to look for wives amongst other ethnicities. The first generation did not mix as much, but the later generations married outside of the community quite often.

Already from the early days of the colony, the younger generations would head off to the big cities in search of work, most often to Chicago, Baltimore, Milwaukee and other American cities. Young people leaving the colony became even more common after the Second World War. As a result, new families were not established in the colony, and its numbers dwindled.

Today, few descendants of the Latvian colonists of Lincoln County still live in the area, but there are instances where people have retired to the area where they grew up. There are also very few speakers of Latvian left, however, most of the older generation do know how to sing the traditional Latvian song “Kur tu teci, gailīti mans” (Where are you going, rooster mine”).